Societal Constraints Be Gone

A History Of Anarchism Series | Part Two

This essay is the second in a thirteen-part romp through the history of anarchism.

Last week, in A Cynic Love Story For The Ages, we left the married Ancient Greek philosophers Hipparchia and Crates old, happy, and cynical as ever. Today, we’re backing-up to consider Hipparchia inverting normative gender roles for her time.

We’ll start with an enduring account of Hipparchia standing up for herself at an Athenian get-together.

The mood at Ancient Greek drinking parties for the elite, known as symposia, was generally chill, hedonistic, and completely male-centric. And no well-born woman attended unless only kin were present, which never happened.1

Except Hipparchia the Cynic—she showed-up to symposia plenty of times.

If you read A Cynic Love Story For The Ages you’ll remember her deal—Hipparchia had picked a Cynic life-partner and defied her parents’ expectations regarding marrying another of their kind; that is, moneyed, respectable, able to keep Hipparchia well-housed, and appropriately served. Her husband Crates afforded her none of these things, that’s the reason why Hipparchia had wanted him in the first place. With him, she turned-toward self-sufficiency and independence from all things unnatural including money, permanent-shelter, silk cloth from a five-thousand-miles-away, and private living.

Hipparchia’s lifestyle, astonishing to her contemporaries, wasn’t so incredibly novel actually. Ancient Greece had its share of unhoused persons existing on the streets. It was her choosing this as freeing, while also naming upper-crust lives restrictive, absurd, and demoralizing that rattled everyone she knew.

Classics professor Sean Corner writes,2

Hipparchia's lifestyle of going about with her husband, dressing like him, appearing with him in public, and accompanying him to symposia, represents an inversion of normative gender roles [even among the Cynics].

Interestingly, there’s no mention in all of Ancient Greek documentation of any kind, across centuries, of any other elite woman ever attending a single symposia. Hipparchia was in her own category, as far as Ancient Greeks went.3 4

But there’s one particular symposium Hipparchia made memorable for philosophers far into the future.

Let’s set the scene:

Relaxing on cushions and scantily-clad in large rooms with high ceilings—sipping watered-down wine, licking feta cheese off each-others fingers, summoning enslaved women and boys standing-by-as-needed for whatever—Ancient Athenian aristocratic men of every age debated politics and ideas at their ultra-exclusive symposia.

Hipparchia walked-in, Crates by her side, both prepared to discuss how to best live. Suddenly, Theodorus the Atheist called-her-out. “Funny seeing you here,” Theodorus said. He didn’t mean “funny, as in ha ha funny.” Nope, he was being an idiot.

Theodorus then asked Hipparchia if she’s that woman he’s heard so much about, the crazy one who abandoned her loom like the brainwashed, drunk, and murderous princess Agave of Thebes from the play by Euripides.

Oof.

Theodorus the Atheist was referencing the well-known tragedy, The Bacchae by Euripides,5 which had premiered in Athens a century earlier.

This is Euripides’ tragedy, the one Theodorus was using to snub Hipparchia:

An Ancient Greek princess—roaming through forests with girlfriends, brainwashed by the vengeful non-binary god of wine and insanity, Dionysus, who was also her nephew—Agave of Thebes had been unwittingly vacuumed-into his cult. This was Dionysus punishing his aunt for spreading rumors about his dead mom, her sister.6

Agave and her two remaining sisters—plus a-hundred-other-followers of Dionysus known as the Maenads—suckle animals, braid snakes in their hair, and rip-apart cattle with bare hands. All this in frenzied worship of Dionysus.

Then the party turns irrevocably gruesome—trigger warning here for what follows.

At the behest of Dionysus, Agave, her sisters, and the Maenads, tear apart Agave’s own son, the King of Thebes. They rip-off his limbs and head, then eviscerate his core. All this in ferocious celebration.

Agave, convinced she’s killed a lion, instead of her grown child, exudes power. Ecstatic, she leads the Maenads to her father, the former King of Thebes, carrying her offspring’s bloodied head on a spike.

But Agave sobers-up in a flash, when she catches the horror on her father’s face.

Hipparchia had seen the play.

She understood Theodorus was insulting her, alluding she was an out-of-control woman, instead of the virtuous shame-free thinker she lived to be. And she wasn’t about to let his affront go unaddressed.

“Yes,” Hipparchia said. “It is she, the woman who abandoned her loom. But,” she asked Theodorus, “is she wrong spending her life on education rather than wasting it on the loom?”

Then she used the philosophical tool of the syllogism on him—a “ha ha” moment of her own. Check out what she said next:

Any action not called wrong if done by Theodorus, wouldn’t be called wrong if done by Hipparchia; Therefore, if it isn’t wrong for Theodorus to hit himself, Hipparchia wouldn’t be wrong if she hit Theodorus.

Left speechless for a second, Theodorus stared at her.

Then Theodorus lunged at Hipparchia.

I’d like to turn our gaze to where Crates—Hipparchia’s husband—was at the moment.

Crates was watching Theodorus belittle his wife in real time, possibly relaxing on cushions like every-other-guy in the room. I’m not judging Crates here, although there’s plenty to unpack—he could’ve been “letting her” try-out her wings without his manly intervention on purpose, for one, or maybe he was engaged in conversation with (or the sensual pleasuring of) another dude—Whatever. Crates didn’t do a thing.7

So, Theodorus lunged at Hipparchia and “tried to strip her of her cloak.”8

Ancient Cynics were against militarization—they didn’t think sacrificing any life for the sake of a state signaled virtue and opposed war altogether. They wanted to abolish money because it promoted systems of domination based on the hoarding of trivial objects with little inherent value (coins).

But Cynics like Hipparchia were most-known for radical living. They made life choices based on the ideals of eleutheria (freedom/liberty), autarkeia (self-sufficiency), and parrhēsia (freedom of speech/frankness). And they scoffed at attempts to shame them as they saw themselves unfettered by social rules. Modesty wasn’t a Cynic thing at all.

Ha.

This is why Hipparchia didn’t panic when Theodorus “tried to strip her of her cloak” in front of the most powerful men of her community. She was indeed an OG Cynic, after all.

We don’t know if Hipparchia physically fought Theodorus off, or if her face registered contempt for him or his boorish act. But five-hundred years after the incident, the eminent biographer of Greek philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius, wrote of Hipparchia’s reaction to Theodorus—She was cool. You know, ‘cause bodies are natural.9

The early Cynics never advocated for all women to unite and live shamelessly, free of social domination. They didn’t suggest the enslaved rise-up against their masters either. They believed rational human-beings—women or enslaved men, too—could embrace a Cynic lifestyle and do what they wanted when they wanted. But not as a group or class of people but individually, and with lots of independent thinking.

Hipparchia and Crates were pessimistic about how much Ancient Greeks could accomplish as independent thinkers. Most people didn’t have what it took, the Cynics believed. Hence our modern use of the term cynic to denote a lack of belief in human capability writ large.

Ancient Cynicism has similarities to at least a couple of recent conceptions of anarchism.

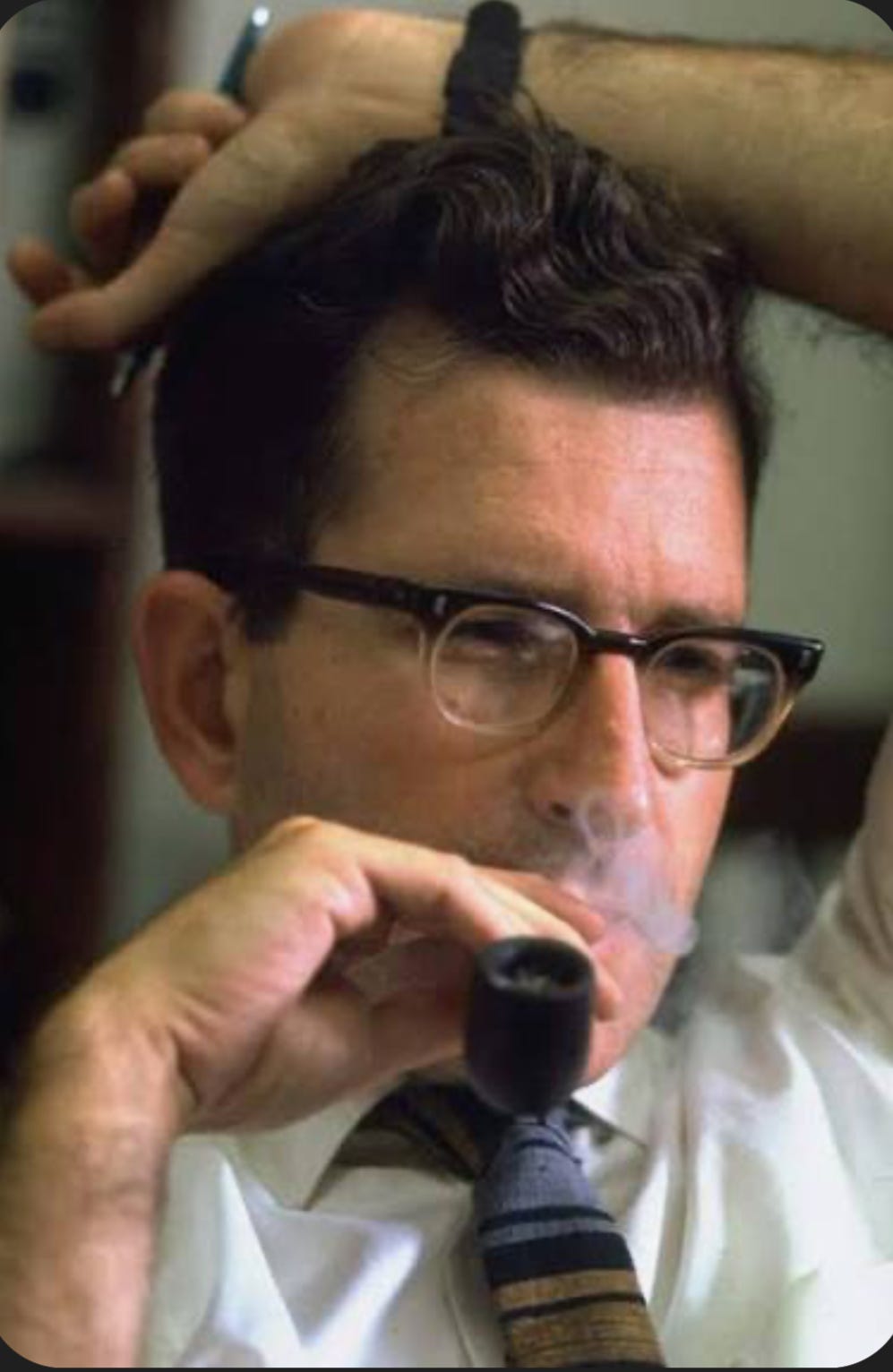

An influential recent anarchist with Cynic tendencies is Noam Chomsky.

While at MIT, Chomsky wore neckties, sweaters, and wool sports-jackets, like any other male college professor. He kept an office full-of-books, worked-for-money, and lived in a proper house. His anarchism had no physical scandal attached, definitely not to the scale of Ancient Greek Cynics like Hipparchia. Chomsky’s children weren’t conceived or birthed by his then wife, Carol, in public, for example.

Chomsky’s frequent public interrogation of systems of hierarchy and domination, or of particular massacres are what’ve set him apart as a philosophical anarchist. He’s been a very vocal political activist in the United States for decades. I actually first read about him in the 1980s in my New York Social Studies textbook.

The man’s alive yet, but in 2023 he suffered a massive stroke and no longer writes or speaks publicly. He and Valeria, his second wife, live in São Paulo.10 Valeria has said he watches global news still, and has been deeply moved by both the current plight of the people of Gaza and transnational protests calling for an end to Palestinian carnage.

I recently came across a 2013 interview of Chomsky in which he defined his brand of philosophical anarchism,11

Anarchism is…a kind of tendency in human thought which shows up in different forms in different circumstances, and has some leading characteristics.

Primarily it is a tendency…suspicious and skeptical of domination, authority, and hierarchy.

It seeks structures of hierarchy and domination in human life over the whole range, extending from, say, patriarchal families to, say, imperial systems, and it asks whether those systems are justified.

What makes Chomsky’s philosophical anarchism align with strains of Ancient-style-Cynicism is his, well, cynicism regarding the vast majority of people’s incapacity for full freedom of thought.

Chomsky has been quite “suspicious and skeptical” of United States “domination, authority, and hierarchy.” He was also gloomy regarding U.S. professors and writers. At the tail-end of the Vietnam War,12 for example, Chomsky wrote, “It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.”13 But, he argued, thinkers in the United States had been bought-off by the military industrial complex,14 and hadn’t done their job for years.15 He also said, “Education is ignorance….that’s what it often is in practice. It shouldn’t be.”16

He wrote journalists were “easily-led, ideological dupes of the powerful” and readers (of most varieties) were victims of their own lack of independent thought.

Cynical thinking indeed, I’d say.

Another subset of today’s anarchists, modern primitivists, also align with Ancient Greek Cynicism in their rejection of social convention, disdain for civilization’s rules, a strong stick-it-to-the-man ethos, and the belief that most twenty-first-century persons can barely think for themselves.

Rejecting social constraints in general and technology as intrusive in particular, primitivists advocate and long-for “natural” living. But they differ markedly with Ancient Cynics in where they do it. Hipparchia and Crates were kosmopolites on the streets of Athens—a city of around 200,000 inhabitants, with citizens, foreign-born residents, and enslaved persons, full of crying babies, laughing teenagers, and yelling merchants. Such urban settings make primitivists break-out-in-hives. They’d rather escape from the masses of non-free-thinkers to forests and deserts.

Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 Walden17 exemplifies this idealized primitivism.

Thoreau published his Walden in Boston, the same year the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed through the United States Congress. The Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to slavery by leaving it up to local vote.

Abraham Lincoln, still a working Illinois attorney in 1854, spoke-up against the naivete of leaving the issue of slavery to direct democracy. The enslaved were real people, he said in a speech in Peoria, with natural rights. Their humanity shouldn’t be up for vote by anyone. Lincoln’s speech began the unification of white abolitionists, free-soilers, and northern Whigs into what became the Republican Party, founded only months later.

Thoreau was himself an abolitionist. While living at Walden Pond, he’d been arrested for nonpayment of the poll tax. Not paying taxes was his protest against government’s complicity in slavery. Before Walden, Thoreau had already published Civil Disobedience, a track arguing for the prioritizing of individual conscience over government, and the right of the individual to refuse financial support to a government overstepping its boundaries.

Still, while Lincoln worked to unite people in a big way, Thoreau was a believer in personal responsibility, with little faith in a formal collective.

Check out what Thoreau wrote,18 19

From hard, coarse, insensible men with whom I have no sympathy, I go to commune with the rocks, whose heart[s] are comparatively soft.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life.

Blessed are they who never read a newspaper, for they shall see Nature, and through her, God.

Thoreau did concede it’s “better to accept the advantages . . . [of human] invention and industry…” and helped his parents perfect their pencil-making to boost their business. But as for free-thinking, he didn’t think this was a common activity in an ever-industrializing and morally-compromised nineteenth-century United States.

Unlike Thoreau, committed primitivists today tend-to not see advantages to large-scale human invention and industry. They generally abhor tech. In his 2009 A Primitivist Primer, for example, John Moore writes,20

Technology is all the drudgery and toxicity required to produce and reproduce the stage of hyper-alienation we languish in.

It is the texture and the form of domination at any given stage of hierarchy.

More recent primitivists turn to Indigenous societies established across the Americas thousands of years ago. They’re convinced these cultures contain inspirations on how to live without artificial constraint, hierarchy, and domination—in nature and far away from twenty-first-century cities, suburbs, and intrusive government.

The 2016 Captain Fantastic is a nuanced film about a fictional primitivist anarchist family. Because Ben Cash, the dad, is controlling and coercive, anarchism’s distilled main meaning—one without leader or ruler—applies to him exclusively.

Ben Cash has no one checking his actions for a good while. But his six kids, he commands them early and often. The older Cash kids have all read Noam Chomsky, and Manohla Dargis of The New York Times noted,21

At its loftiest, [the Cash family’s] profound seclusion suggests that they’re spiritual and philosophical heirs to an isolationist like Henry Thoreau.

Like Thoreau, Ben Cash is self-deferring, but unlike the author of Walden, who in actuality wasn’t isolated at all—but threw melon parties featuring his own delicious watermelons, attended literati dinner parties with Louisa May Alcott’s family and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and whose mother washed his laundry and made him breakfast—Cash demands his family live as survivalists, with scant outside human contact, on principle.

Hipparchia was clearly not a primitivist—at least not in an extreme getting-back-to-nature sort of way. Although Ancient Cynics discarded the ease and comfort of “civilization,” they weren’t looking to isolate from humanity itself. Instead they worked to shed societal restraints (including sexual privacy) within community, on its streets and in its symposia.

The idea of philosophical Cynicism itself isn’t aging well apparently. Philosopher David Mazella writes,22

Modern cynicism [has] come to describe something antithetical to its previous meanings, a psychological state hardened against both moral reflection and intellectual persuasion.

Still, some of today’s anarchists—especially intellectual and primitivist—claim Ancient Cynic influence.

We’re going to move on from the Ancient Cynics and their possible influences on anarchist modernity.

A thousand years after Hipparchia had faced Theodorus at the symposium, so much had happened over a millennium. The Roman Empire had risen and fallen, Hipparchia’s Athens had been invaded by Slavic and Norman tribes, and then Crusaders kept trying to conquer the region for Christ by force.

The Ancient Greek word anarkhia became Christianized as anarchia in Medieval Latin.23 And during the early Middle Ages, anarchia described the status of God himself. The Lord of Creation was “without a beginning,” Christians believed. He existed in anarchia.24 Smatterings of twenty-first century anarchists cite such thinking, but especially the Medieval Catholic friar from Assisi—Francis—as their first inspiration towards anarchy.

Francis of Assisi turned away from his society’s ways-of-living both philosophically and in action. He vowed to exist “without earthly goods,” gave-away all he owned, and lived like a beggar—because that’s how Christ lived.

But the religious order Francis founded, the Franciscans, lived not by their own free-thinking at all. They had Assisi’s The Rules of The Friars Minor 1210-1222 to follow.25 And Francis’ commitments to abstain from sex forever and to obey the “Holy Pope Innocent,” make him an unlikely intellectual ancestor of today’s anarchism in my humble opinion.

Interestingly, a friend and neighbor of Francis of Assisi, Clare of Assisi, also founded a religious order, The Order of Poor Ladies. She and Francis chatted regularly on how to live the Christian life. And he helped her figure out how to guide her followers appropriately. Clare wrote her own Rules of Life for the Poor Ladies, and this book became the first recorded set of Medieval monastic guidelines known to have been written by a woman.

Francis and Clare became celebrated in their own lifetimes and tales of their powers—she levitated at will, he resurrected people from the dead—abounded for centuries. Both Francis and Clare were eventually canonized as Catholic saints too. And the beloved (and recently deceased) Pope Francis (whose birth name was Jorge Mario Bergoglio) took his papal name from “the man of poverty, the man of peace, the man who loves and protects creation;” that is, Francis of Assisi.

There’s also “a hilarious and poignant modern spin on on the medieval story of…Clare of Assisi,”—the play, Poor Clare by Chiara Atik, which premiered in Los Angeles four years ago. I first heard about it last spring when my son was producing his college theater department’s version of Poor Clare.

When asked why she decided on this particular story, Atik said,

I was having a lot of conversations with my friends in which we would despair about everything from income inequality to homelessness to the refugee crisis and famine in Yemen. We would get ourselves all worked up over dinner, and then I’d go back to my apartment and turn on Netflix and resume my normal life. This reminded me of the story of St. Clare who became radicalized as a teenager, at 18. She didn’t just feel bad about the state of the world, she had the conviction—and strength—to actually sacrifice for what she believed in.

Eric Gordon, a reviewer of Poor Clare for People’s World, thought the play’s characters could’ve come straight out of the anarchist Occupy movement of ten years ago.

Apparently the stories of both Francis and Clare still resonate.

I’ll leave you with lines from Henry David Thoreau’s primitivist poem, Nature, and then a 2014 photo of an Indigenous man living as his ancestors did long ago, on the Amazon in South America, with limited government intrusion even today, at least for now.

For I’d rather be thy child

And pupil, in the forest wild,

Than be the king of men elsewhere,

A woman's participation in Ancient Greek symposia was proof she was a hetaira, a courtesan. See Corner, Sean. “Did ‘Respectable" Women Attend Symposia?” Greece & Rome 59, no. 1 (2012): 34–45 here: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23275154

See Corner, Sean. “Did ‘Respectable" Women Attend Symposia?” Greece & Rome 59, no. 1 (2012): 34–45 here: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23275154

Historians have debated if this is due to a misogynistic erasure of ‘respectable’ women from the record or to them actually not attending symposia at all for real. The second view seems to have won. See Corner, Sean. “Did ‘Respectable" Women Attend Symposia?” Greece & Rome 59, no. 1 (2012): 34–45 here: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23275154

Lastheneia of Mantinea and Axiothea of Phlius (who wore men’s clothing) were pupils of Plato and might have attended a philosophers symposia, but there’s no written record of it. Pythagorean and Epicurean communities may have included female members in their conviviality, even in symposia, but there is again no written evidence they did so.

Listen to this 2021 Let's Talk About Myths, Baby! Podcast interview of UCLA Classics and Dramaturgy Professor, Emma Pauly, “Nonbinary Dionysus, a Look At Euripides' Bacchae with Emma Pauly” here: https://youtu.be/Y9j1BwanBGs?si=VlcKejMjnnbe68vU

According to The Bacchae by Euripides, Dionysus aimed to clear both his mother’s name and to secure his own place in the Ancient Greek pantheon of divine beings. His father was Zeus, Dionysus knew this, but his mother’s family, including Agave and her son, the King of Thebes, said this was a lie. Agave’s (now dead) sister had had a child with a mere mortal dude, not Zeus, they said. Therefore, Dionysus wasn’t a god at all, but a regular out-of-control young guy.

Maybe I am judging Crates, after all.

Check out the entry on Hipparchia (fl. 300 B.C.E.) in the peer-reviewed Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy for more, here: https://iep.utm.edu/hipparch/#:~:text=Hipparchia%20is%20notable%20for%20being,her%20husband%2C%20Crates%20the%20Cynic.

Read more about Hipparchia in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, here: https://iep.utm.edu/hipparch/#:~:text=Hipparchia%20is%20notable%20for%20being,her%20husband%2C%20Crates%20the%20Cynic.

Sadly, Noam Chomsky suffered a massive stroke two years ago and now he and his wife Valeria, live in her native Brazil, in Sao Paulo. Read the Associated Press’s 2024 version of this here: https://apnews.com/article/noam-chomsky-hospitalized-stroke-recovery-brazil-4fb6782abf6a7b6d0bbb30cefa05cede

Read the full Noam Chomsky 2013 interview by Michale Wilson, “The Kind of Anarchism I Believe in, and What’s Wrong with Libertarians,” here: https://chomsky.info/20130528/

The Vietnam War lasted from 1955 –1975.

See Noam Chomsky’s 1967 “A Special Supplement: The Responsibility of Intellectuals” in The New York Review of Books, available here: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1967/02/23/a-special-supplement-the-responsibility-of-intelle/

See Chomsky’s American Power and the New Mandarins (1969)

Chomsky was especially disgusted by the roles of the fields of psychology, sociology, systems analysis, and political science in making extreme U.S. militarization ok.

Read Noam Chomsky’s 2011 interview by Jennifer Pagliaro here: https://chomsky.info/20110604/

See Henry David Thoreau's iconic Walden (1854).

From Henry David Thoreau’s Journal entry for 15 November 1853

From Thoreau’s letter to Parker Pillsbury, dated 10 April 1861

Read her 2016 NYT “Review: Viggo Mortensen Captivates in Captain Fantastic” here: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/08/movies/captain-fantastic-review.html

See The Making of Modern Cynicism by David Mazella (2007)

See Peter L. Smith’s 1997 “The Legacy of Latin: II. Middle English” available here: https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/greeklatinroots/chapter/23-the-legacy-latin-middleenglish/

See Peter H. Marshall’s Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (1993)

See Internet Archives’ 1907 version of The Writings of St. Francis available here: https://archive.org/details/writingsofstfran00fran/page/n31/mode/2up?view=theater