Earlier this week, a line in my daughter’s Human Geography study-guide made my jaw drop. I was quizzing her for the final, and couldn’t believe what I’d just read.

“What?” she laughed seeing my reaction.

Twenty-first century historians are very aware of our role in shaping history. We can’t keep everything that’s ever happened in the narrative, be it oral or written. We’re compelled to choose what stays in the story so it actually makes sense to another. Granted my kid was studying high school Geography, not History.

Still, what I’d just read made my head turn.

“What role do women play in demographic change?” I said. “Isn’t this a ridiculous question? What role?”

I would’ve relished monologuing on how the response in her study guide—population decreases when women are educated—is an erasure of a crucial human labor.

But, I restrained myself. The sun was setting over the western mountains and the sky outside had turned purple. We had a ways to go in the study guide before her bedtime. So I made a quick jab instead.

“We give birth!” I said. “That is how we affect demographic change.”

One of my undergraduate students stops by my office regularly to discuss research on what he calls “the Early Christian Fathers.” This isn’t my area of expertise—the second century CE male founders of Christianity—but I enjoy chatting with him and contributing to the conversation by suggesting he also read the mothers.

Recently, while checking-out further readings to offer him, I came across lovely new histories on the Roman Empire. My sixteen-year-old daughter gifted me A Rome of One's Own: The Forgotten Women of the Roman Empire by Emma Southon on my birthday, and I’m loving it.

Another lovely new history now in my possession is Anna Bonnell Freidin’s Birthing Romans: Childbearing and Its Risks in Imperial Rome.1 She writes,

The majority of women in the Roman empire, as in countless premodern cultures globally, spent much of their adult lives in an inexorable cycle of pregnancy, birthing, childrearing, and mourning.

In grad school, this perilousness of historical pregnancy, birthing, and childrearing, was eye-opening.

Since then and through the years, I’ve noted pretty much every family in the British American colonies, for example, experienced tremendous loss related to the cycle of life. So many people in the past never made it to the age I am today.

I think of Abigail Adams, a founder of the United States who gave birth to six children. She and her husband, President John Adams, lost half their immediate family. One child was stillborn, another died as a toddler, and a third of breast cancer as a young adult.

Out of Martha and Thomas Jefferson’s six kids, only a daughter made it adulthood. And Martha herself died after giving birth to their sixth child.

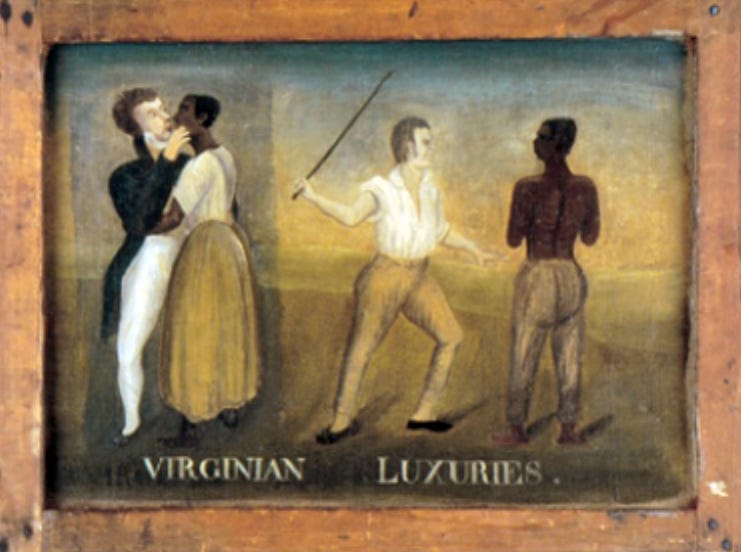

Sally Hemings, Jefferson’s enslaved partner, gave birth to seven children. Four lived past two years old.2

The Ancient Romans had their famous Vestal Virgins, adults with uteri whose bodies wouldn’t participate in the cycle of life-and-death as other women. Instead, they nurtured the goddess of birth, Vesta. She lived in the world as fire and burned within her own temple’s hearth day and night.

Interestingly, the Vestal Virgins received an awesome education inside Vesta’s temple.

But truly, the birthing years of roughly half-the-population were fraught with peril for all involved, for thousands of years.

A little over a year ago, a TikTok trend showed 4% of men in the United States think about the Roman Empire daily. I chuckled when I read “only 1% of U.S. women do so,” also daily. I find this a bit of trivia fascinating and incredible at once. I can’t stop thinking about it. And also, where are these three million women thinking about the Roman Empire at least once-a-day? Not in my small corner of Southern California, that’s for sure.

But I digress.

In any case, I’m pretty sure most people thinking about Imperial Rome in the twenty-first century aren’t considering issues and experiences surrounding Roman birth. Ancient Roman soon-to-be fathers did, of course. They had a profound anxiety about childbirth and early infancy. So much life was constantly at stake.

Ancient Roman soon-to-be fathers had a profound anxiety about childbirth and early infancy. Of course they did. So much life was constantly at stake.

If a Roman husband consulted the Oracle of Astrampsychus 3 to ask, “Is my wife having a baby?” The Oracle answered with one of the following predictions:

She’ll give birth with danger

She’ll give birth to a beautiful baby and do well

She’ll give birth and the baby will survive

She’ll give birth to a boy with danger

She’ll give birth with great danger

You’ll father a baby, but the baby will be unhealthy

She’ll have a baby girl who will quickly die

She’ll have a baby girl with danger

She’ll give birth and be in danger up to the point of death

She’ll give birth and the baby will be unhealthy

During my first pregnancy—I was 27—I didn’t feel emotionally ready for matrescence.4 I’d recently enrolled in grad school, worked full time, traveled, was newly married.

I worked out.

Having a child would be a point-of-no-return for me, I knew. I’d been this for my own mom. “In a wonderful way,” she’d told me. “I’d wanted to be a mamá for so long.”

Living in 1996 California, I had choice.5

Despite my early ambivalence, I gave birth to a gorgeous baby that Spring. And I loved her with all my heart.

Still, I’d no idea how epic an odyssey6 giving birth had been for humans since the beginning of time. The thing is, the history of birth hadn’t been part of my mainstream American education. If I’d read a high-school-Geography-study-guide back then, would I have paused on reading questions about women’s role in demographic change? I don’t think I would’ve caught the irony.

Here are some things I’ve learned since then:

In the time of Christ, the average life expectancy was roughly twenty-five years old. People died in childbirth and more often, in the days or weeks after, due to infection.7 Children had about a fifty-percent chance of living past five years old, largely due to infections and infectious diseases. Men died in battles, and soon after due to wound infections. All kinds of people died in accidents of all kinds or soon after, due to (bet you can guess) infection.

Life and death have indeed been a tight cycle through the ages.

Then, less than a century ago—in 1937—mortality rates for women and children especially began plummeting.8 What happened?

One word: Antibiotics.9

Also improved obstetrics, nutrition, hygienic practices and pediatric care.

People whose bodies create new people still perish in childbirth and soon after, all over the planet. Although much less so today than in the age of your great-grandparents if you’re ancestry is from in South America, Europe, Asia, and/or North America. 10

Back to the Roman Empire.

The Ancient Romans celebrated birth big time—maybe because of how magnificent it was when things went well.

There was the holiday of Matronalia in March, a huge, empire-wide party celebrating mothers (as long as they were married)11 and birthing. On this day, at the Temple of Vesta, the Vestal Virgins put-out the sacred fire on the hearth and promptly re-lit it.

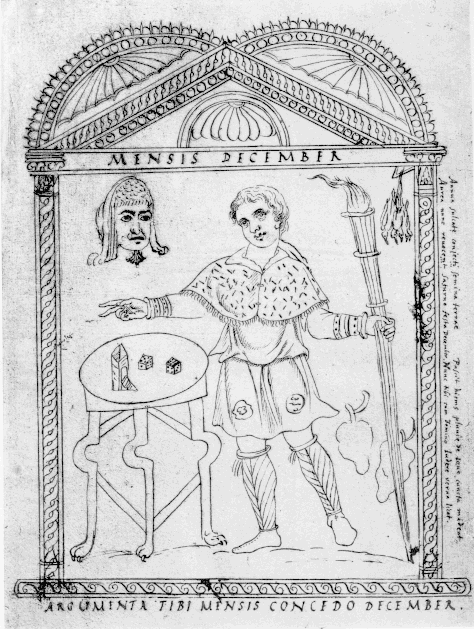

A festival celebrating the earth giving birth to grains, vegetables, and fruits, celebrated in December, was Saturnalia.

The Ancient Romans also partied with friends and family on their personal birthdays. And on December 25th, they celebrated Dies Natalis Solis Invicti—“The Birth of the Invincible Sun.” This holiday morphed-over-time into what we, two thousand years later, know as Christmas.12

Several centuries after the apex of Ancient Rome, Christianity had spread across the former Empire. But the religion was in trouble, especially in what today we call Spain—Hispania.13 And birth, well, it threatened lives, families, and entire kingdoms as ever. Even in Mediterranean Europe.

In Hispania, in the year 1240 CE, a sixteen-year-old’s legs swelled. The pain was too much.

The teenager dipped into a nearby saltwater spa for relief, with a small statue of the Virgin Maria in hand, and was healed from the swelling and hurt.

Prince Alfonso—whose beloved mother had died two years before—had possibly stood too long on the battlefield with his father as they reconquered the Kingdom of Seville in southern Hispania, from the Moors.14 Alfonso might’ve been dehydrated, too. The result was what doctors today might call bilateral lower extremity inflammatory lymphedema,15 a swelling of the legs.

In any case, Alonso, who became King Alonso X of Castile (also known as Alonso the Wise) attributed his relief to the Virgin Mary. As King, he commissioned and composed the first carols in the Virgin’s honor.

The Cantigas de Santa Maria16 or Canticles of Holy Mary: 420 poems in Early Medieval Galician-Portuguese (popular in Castile at the time) were written with musical notation during the reign of King Alfonso X. Historians have confirmed he wrote many of them himself.

These compositions had a single musical line, without accompaniment, like a solo Gregorian Chant, and every tenth song was for group singing, a hymn. The Cantigas de Santa Maria were precursors of the French virelai and Muslim Spain’s zajal, and they went on to inspire musicians for centuries.

But what interests me most about King Alonso X and his Cantigas, is the epic Maria he venerates. She’s a force. More like an Ancient Roman goddess giving birth to the invincible sun. She’s powerful and demands attention.

Alonso’s Mary is also much like Violant of Aragon, his educated (but so very young) wife. Violant stands with Alonso in war—and gives birth to eleven children (several in battle grounds). Half of their babies never live to adulthood.

At one point, Violant marshaled armies against Alonso, to secure their son’s throne (he wanted his grandson to follow him). The epic Violant won this battle.

The Virgin of Alfonzo’s Canticles mirrors his educated mother, Elisabeth of Swabia from what is now Germany, as well. She became Queen Consort of Castille, educated Alonso herself, and died at 30 years old after giving birth to her tenth child.

Alonso had been very close to his mother, and remembered her the rest of his life.

The Virgin Mary of Alonso X’s Canticles is epic.

She’s been through odysseys.

This Hispanic King surrounded by fascinating women, also wrote Spain’s first codes of law, the Siete Partidas. Alonso X’s codes allowed married women to own property in their own name—the rest of Europe did not for hundreds of years. The Siete Partidas were law, centuries later, in Colonial Spanish America, including in what are now the states of Louisiana, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. These states still have codes of law citing Alonso’s Siete Partidas, including those pertaining to women owning property in their own name.

As a reference, none of the initial thirteen states of 1783—where Abigail Adams, Martha Jefferson, and Sally Hemings gave birth—allowed married women (mothers or not) to own property.17

I’m thinking again of Anna Bonnell Freidin’s quote from earlier.

The majority of women in the Roman empire, as in countless premodern cultures globally, spent much of their adult lives in an inexorable cycle of pregnancy, birthing, childrearing, and mourning.

Violant of Aragon, Elisabeth of Swabia, Abigail Adams, Martha Washington, and Salling Hemmings—courageous women in their own times, all of them also “spent much of their adult lives in an inexorable cycle of pregnancy, birthing, childrearing, and mourning.”

Could this be why theVirgin Mary has been an icon of humanity for over a thousand years?

In the early Christian centuries—as “the Early Christian Fathers” disputed whether Christ could’ve been human in any way, his mother, the woman who birthed him, became pivotal in theologically-proving Jesus had truly been a human being (and not “just” God).

If Mary gave birth to Jesus, he had to be human, the argument went. This view has prevailed in Western Christianity ‘till today.

Recently, the Austrian artist Esther Strauß commissioned sculptor Theresa Limberger to commemorate the human sides of the Virgin. The most controversial of which is the piece titled “crowning” depicting the subject giving birth. Strauß writes,

Mary is perhaps the woman in the world of whom there are the most paintings, drawings and sculptures; there must be thousands upon thousands. The majority of these images were made by men.

Why does the image that is missing stand out among them?

The above work was meant to make people think about traditional portrayals of the Virgin Mary and to challenge the meek and mild interpretations often seen in Christian art.

The sculpture of Mary giving birth angered some. She was brutally decapitated in June of 2024. Such an act, as metaphor for current birth debates of all kinds, sends shivers up my spine.

I think of the pregnant in Gaza and in Jerusalem, too. The expecting in Mississippi, Texas, and the Congo. The women laboring surrounded by familial support in South America and the lonely young wives in Indiana. Because giving birth is a big deal. It always has been.

Again, I consider the pre-modern Roman women in “an inexorable cycle of pregnancy, birthing, childrearing, and mourning.” And the Early-Modern mothers of the United States.

Why wouldn’t we want to at least think about, if not celebrate, birth—our own and everyone else’s—after all we’ve been through, as a species. I don’t think I’m being too dramatic here.

Sixteen-hundred years ago, a Roman artist recorded the feast celebrating the birth of Christ on December 25.18 19 The Empire had turned Christian and had fallen soon after. Still, they celebrated birth. Only one, really.

But, is celebrating a single birth better than total erasure of a reoccurring and monumental human event—the labor of millions across time to bring humanity into the future over and over? I think not.

Peace on earth, and goodwill to us all—whether we give birth, or not.

See also Kyle Harper's The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (Princeton Univ. Press, 2017) and Emma Southon’s A Rome of One's Own: The Forgotten Women of the Roman Empire (Harry N. Abrams, 2023).

See Sally Hemings page on the Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello site, here: https://www.monticello.org/sallyhemings/

A then popular handbook

Matrescence is the physical, emotional, hormonal and social transition to becoming a mother.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that same year, California passed a law permitting non-profit hospitals, medical facilities, and religious doctors and nurses to refuse to provide abortion services on religious grounds.

The epic Ancient Greek poem by this name follows Odysseus, king of Ithaca, and his journey home after the Trojan War. But my mother used the lower case word to denote extreme lived drama, that’s how I’ve used it here.

In the early 1800s this became known as “puerperal fever.”

Check out for a science article on this: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10871589/

See this article on the medical history of antibiotics: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1369527419300190#:~:text=The%20first%20antibiotic%2C%20salvarsan%2C%20was,peaked%20in%20the%20mid%2D1950s.

See UNICEF’s maternal mortality statistics here: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/

Commonwealth Fund’s Comparison of Europe against the United States here: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison

Of course I see the problem here. It was a different time.

See the Sol Invictus and Christmas page of the University of Chicago’s online Encyclopaedia Romana for more details on this.

Hispania was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula.

North African Arab Caliphs (or Moors), had taken southern Spain from the Christian Hispanics (hispalenses in Spanish) in 711 CE.

Read this condition described (in today’s soldiers) in Caroline E. Moore’s article, “Inflammatory Lymphedema Masquerading as Bilateral Cellulitis: A Military Dilemma,” in the January 2024 issue of Cureus. Available at: doi: 10.7759/cureus.51743

From Manuel Pedro Ferreira’s “The Medieval Fate of the Cantigas de Santa Maria: Iberian Politics Meets Song” in the Journal of the American Musicological Society (2016) 69 (2): 295–353.

And yes, one of these women was considered property herself. She didn’t even own her self.

I’m referring to the Calendar of 354 by the calligrapher and illustrator Furius Dionysius Filocalus created for a wealthy Roman Christian, Valentinus. See it at The Tertulian Project here: https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_06_calendar.htm

For an interesting scholarly discussion of the dawn of Christmas (from an Orthodox Christian pov) see the Orthodox Academy of Crete’s 2023 Special Christmas Edition article by Mark Beumer, “From Mithras to Jesus: Ritual Dynamics of Christmas,” in AC: After Constantine. Check it out here: https://www.afterconstantine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/AC-Christmas-2023.pdf.pagespeed.ce.KJPp7O_s5E.pdf#page=16